Context

Wind energy heralded India’s renewable energy journey. The country’s first grid-connected wind energy project was commissioned in 19851, decades before solar energy arrived on the scene. With continuous central and state government support, the wind energy sector has grown tremendously over the years. However, growth in recent years has been muted and has notably lagged behind solar. One of the reasons is the fast depletion of sites with attractive wind resources. Wind repowering can address this challenge by facilitating increased generating capacity on sites with such attractive wind resources.

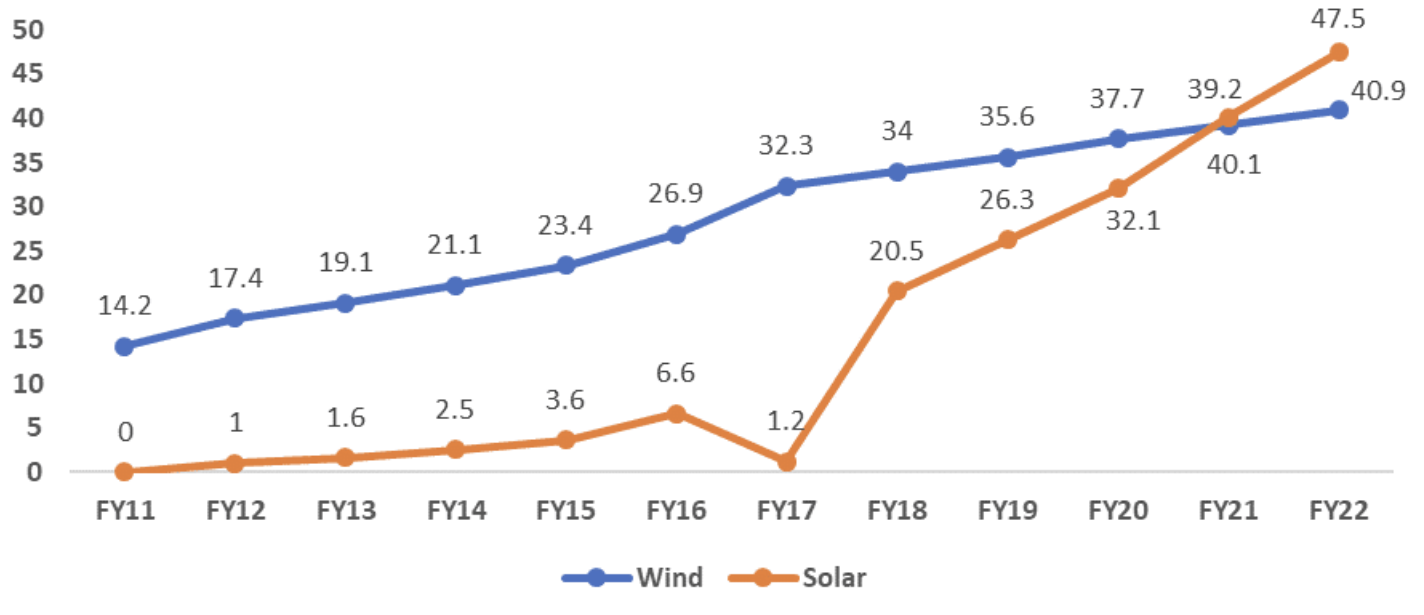

Figure 1: Utility-scale wind installed capacity in India (GW)

Source: Ministry of New & Renewable Energy

What is wind repowering?

Replacing outdated wind turbines with modern and updated turbine technology is known as wind repowering. It is further classified as full and partial repowering. In full repowering, the existing wind turbines are dismantled, and new wind turbines are installed. In contrast, in partial repowering (lifetime extension), some components, such as the generators of existing wind turbines, are upgraded. Full repowering usually results in an increase in generating capacity on the same land footprint.

In India, wind energy projects installed before 2000 at the best wind sites predominantly have a capacity below 500 kW and a hub height of 50 m or lower. This results in maximum achievable plant load factors (PLF) of below 20 per cent. However, significant increases in capacity and PLF are achievable at higher hub heights.

For example, the National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE) estimated India’s gross wind power potential in seven windy states2, namely, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. At 100 m, NIWE pegs the potential to be 302 GW. It further estimates that increasing hub height by a mere 20 per cent to 120 m can result in a potential capacity increase of over 100 per cent to 695.50 GW.

To promote the optimum utilisation of wind energy resources and address evolving challenges regarding land availability, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE)3, released a repowering policy for wind power projects in 2016. According to this policy, wind turbine generators of 1 MW or below capacity are eligible for repowering. Eligible projects will receive incentives such as interest rate rebates from the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) and other benefits that are available to Greenfield wind energy projects.

At the state level, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu have also identified the value of repowering their old wind power projects. For example, in 2018, Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation Limited (TANGEDCO) released its own draft repowering guidelines4. The very same year, Gujarat also released its state wind repowering policy5. Separately, Rajasthan6, Maharashtra7, and Andhra Pradesh8 have included references to repowering in their wind power policies.

Internationally, many countries have initiated wind repowering; the key markets in Europe for repowering are the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and France. In addition, wind repowering is also becoming a common phenomenon in the United States9.

Relevance to India’s renewables trajectory

The wind energy sector is expected to play a prominent role in India’s energy sector transition. Consequently, the adoption of wind repowering becomes inevitable. As per the updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC)10, India committed to transitioning to 50 per cent cumulative installed power generation capacity from non-fossil-fuel-based resources by 2030. Additionally, the Central Electricity Authority’s report (launched in January 2020) on the optimal generation capacity mix for 2029–30 highlights that solar and wind energy are expected to contribute 280 GW and 140 GW, respectively11.

Who should care?

Policymakers

Wind project developers

Wind original equipment manufacturers (OEMs)

Investors

References

- [1] Saji, Selna, Neeraj Kuldeep, and Akanksha Tyagi. 2019. A Second Wind for India’s Wind Energy Sector: Pathways to Achieve 60 GW. New Delhi. Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

- [2] Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. ” Policy for Repowering of the Wind Power Projects.” https://mnre.gov.in/img/documents/uploads/c71fc782913649efa6ee5bed9b9c2f26.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- [3] Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Policy for Repowering of the Wind Power Projects, https://mnre.gov.in/img/documents/uploads/c71fc782913649efa6ee5bed9b9c2f26.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- [4] TANGEDCO. “Proceedings.” https://www.tangedco.gov.in/linkpdf/bpno46.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- [5] Gujarat. “Gujarat repowering of the wind projects policy.” https://guj-epd.gujarat.gov.in/uploads/Repowering_of_the_Wind_Projects_Policy.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- [6] Department of energy, Rajasthan. “Rajasthan wind and hybrid energy policy.” https://energy.rajasthan.gov.in/content/dam/raj/energy/rrecl/pdf/Home%20Page/Rajasthan%20Wind%20and%20Hybrid%20Energy%20Policy2019.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2021.

- [7] Maharashtra Energy Development Agency. “Comprehensive Policy for Grid-connected Power Projects based on New and Renewable (Nonconventional) Energy Sources 2015.” Accessed August 24, 2021.

- [8] New & Renewable Energy Development Corporation of Andhra Pradesh. “Andhra Pradesh wind power policy 2018.” https://www.nredcap.in/PDFs/Pages/AP_Wind_Power_Policy_2018.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2021.

- [9] IRENA. “Future of wind.” https://www.irena.org/-/media/files/irena/agency/publication/2019/oct/irena_future_of_wind_2019.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2021.

- [10] Press Information Bureau. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1847812#:~:text=India's%20updated%20NDC%20will%20be,on%20both%20adaptation%20and%20mitigation. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- [11] CEA. “Optimal generation capacity mix for 2029-30.” https://cea.nic.in/old/reports/others/planning/irp/Optimal_mix_report_2029-30_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.