Click here to visit CEEW-CEF Open Access Tools and Resources

India’s ambition is to have an installed renewable energy capacity of 175 GW by 2022, of which 160 GW would be from solar and wind energy alone. However, at present, the total installed capacity of solar and wind energy stands at 72 GW, with a cumulative renewable capacity of 86.7 GW as of February 2020. To meet its targets, India’s capacity must grow at a cumulative aggregated growth rate (CAGR) of 45.6 per cent until FY 2021–22. Despite this mammoth target, the pace of capacity addition continues to be sluggish, due to various risks. In a recent CEF analysis, we highlighted how discoms’ payment delays to renewable energy generators act as one of the major barriers to scaling up renewable energy in India.

Open access is a possible solution to circumvent this risk. An alternative mechanism to the conventional power system, where generators can bypass the counter-party risk posed by discoms1, open-access regulations provide any electricity consumer or generator non-discriminatory access to the transmission and distribution system. Under the current open-access regulations, a large consumer (typically with a minimum load of 1 MW) may procure electricity either from a third party (by signing bilateral agreements for power purchase) or set up their own (captive/group captive) power plant. They can use the state/central transmission and distribution network to supply this power. Under the current regulation, a consumer may procure power on a short-term basis (up to a month), medium-term basis (three months to three years), or long-term basis (12-25 years).

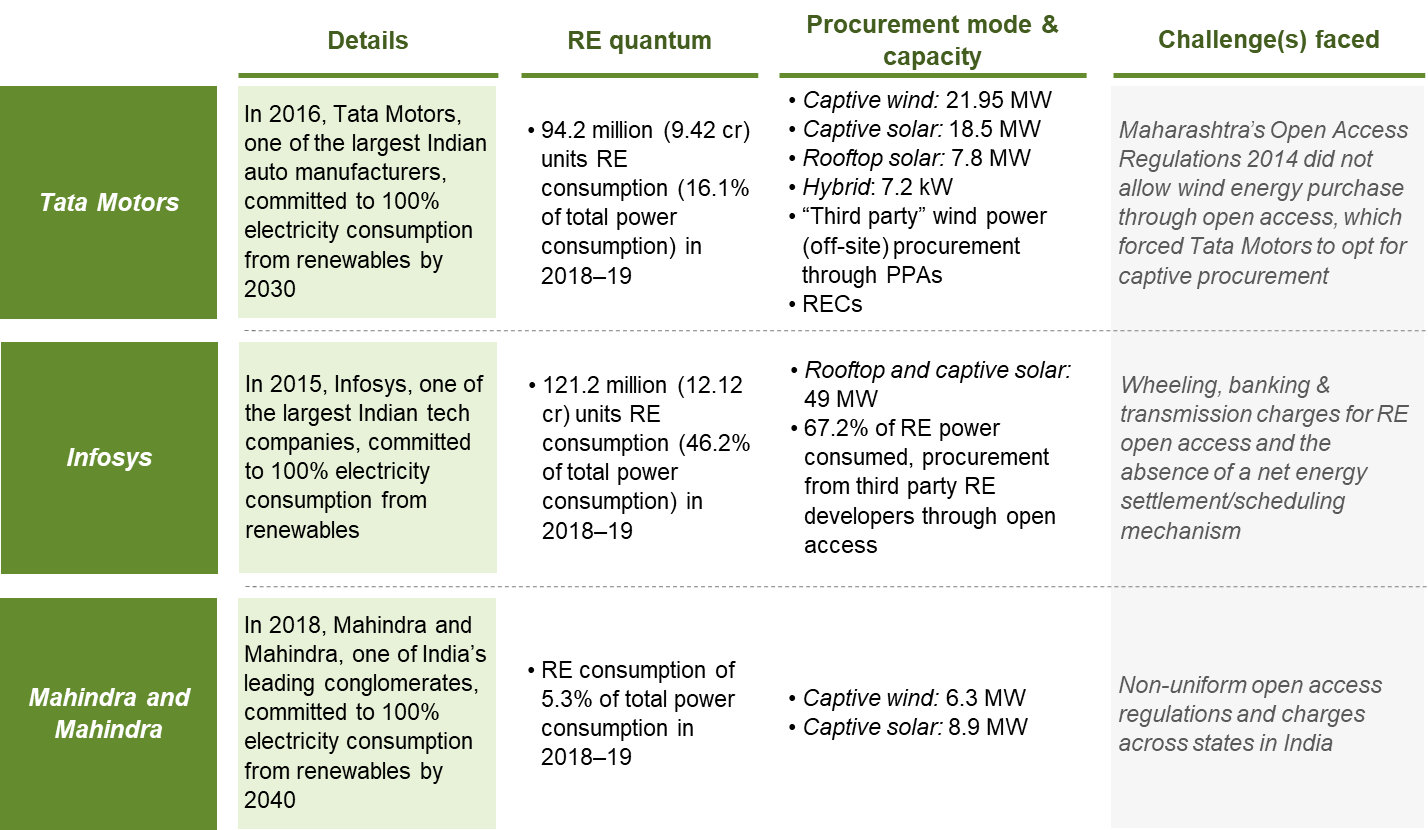

Large consumers (with a load > 1 MW ), especially those paying commercial and industrial (C&I) tariffs, account for nearly 50 per cent of the total electricity consumption in India. With the recent discovery that renewable energy tariffs lie in the range of INR 3 per unit, we have observed C&I consumers shift to open access2. Over the last few years, many Indian corporates have pledged to consume power generated from renewable energy. Companies like Tata Motors, Infosys, and Mahindra and Mahindra have committed to 100 per cent renewable energy consumption (refer to Table 1). Still, uncertain/high open-access charges3 pose a key challenge, with varying state policies inhibiting the broader adoption of open-access regulations.

Table 1: Renewable energy open access case studies

Source: Annual and sustainability reports of companies, 2018-19

How open-access charges in different states stack up

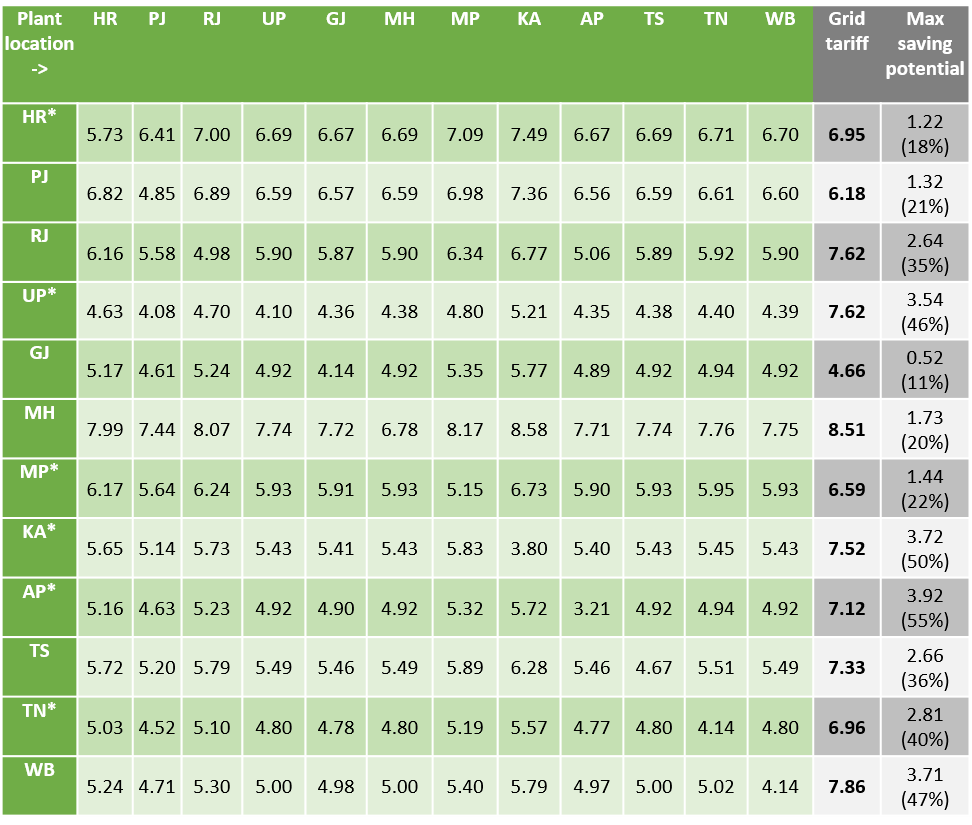

To understand the economics of open access in renewable energy, we compared open-access tariffs with discom tariffs in RE-rich states. We calculated the tariffs (computed in INR per kWh) assuming a third-party solar project with a generation cost of INR 3 per kWh and a 1 MW industrial consumer (or an 80 per cent load factor).

In our analysis, we found that open-access regulations and charges vary significantly across the states. Additionally, many states (marked with asterisks in Table 2) do not allow inter-state open access due to potential revenue losses for state discoms4. We observed that while states such as Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have low open-access charges, other states, such as Gujarat, Haryana, and Maharashtra, offer incentives on the lower side.

Table 2: Tariff (INR per kWh) for industrial consumers under third-party open access, based on the location of the consumer and solar power plant

Source: Author’s analysis based on tariff orders

Market trends

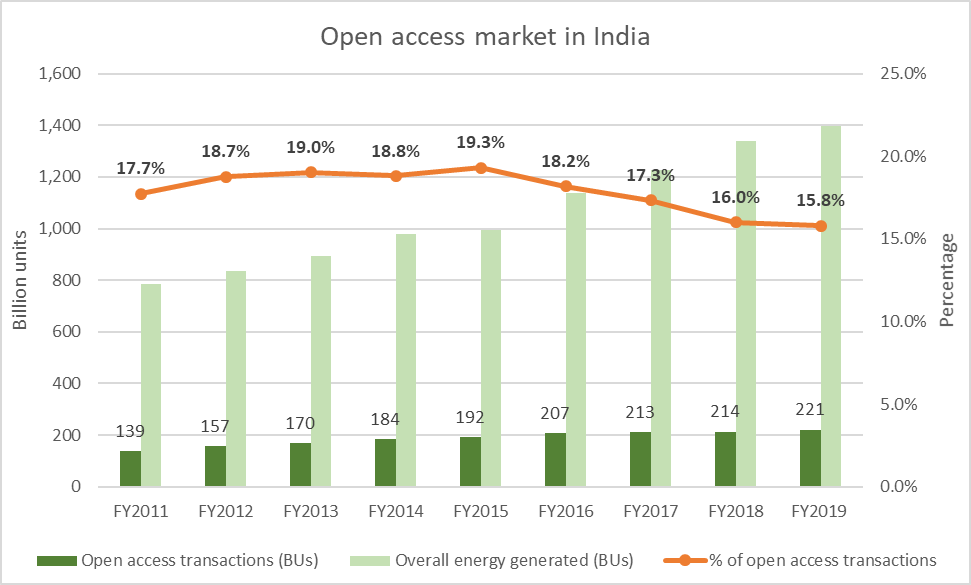

In the past three years, despite increased participation in terms of the number of consumers, we have witnessed a rapid decline in open-access transaction volumes (see Figure 1) with respect to overall power generation in India. The primary reason is the 2016 revision of the cross-subsidy surcharge5 formula under the National Tariff Policy. Also, as of FY 2019, nearly 85 per cent of open-access transactions took place under the group captive mechanism6; only one per cent was through third-party bilateral sale contracts. This was primarily due to the increasing cross-subsidy surcharge, a key component of open-access charges that is waived off for captive/group captive consumers. We have observed that despite policy direction to reduce it progressively, the charge has only increased over last few years.

Figure 1: Open access market in India

Source: CEA reports, CERC MMC reports and regional energy accounts

Key findings

Our analysis suggests that there are four key challenges to an open-access-based renewable energy scale-up and possible solutions are proposed.

A. Consumers frequently switch between open access and regulated supply

With surplus power in the grid, the price of electricity on exchanges has fallen substantially. Large consumers have started to take advantage of this low price by using short-term open access to get less expensive power from the market when the price is lower than the discom’s tariff (even with open-access levies added). These consumers switch part—or all—of their load back and forth between the market and discom, increasing discoms’ difficulties in planning, stranding their generational capacity, disrupting grid stability, and negatively impacting small consumers of the discom.

Recommendation: Avoid regular switching between open-access and regulated power supply; once a consumer shifts to regulated supply, they should not be allowed to switch back to open access for a specified duration.

B. Frequent revision of open-access charges

Frequent changes in open-access charges (especially cross-subsidies and additional surcharges) prevent consumers from entering into long-term contracts with generators or developers. Also, non-tariff barriers—for instance, mandatory continuous withdrawal for a minimum of eight hours, mandatory round-the-clock scheduling, and high standby charges—also discourage open access. Though the National Tariff Policy 2016 prescribes a progressive decrease in cross-subsidy surcharge, in most states, these surcharges have steadily increased. This serves as a major financial barrier for consumers.

Recommendation: Discoms should design a roadmap to phase out cross-subsidies over the next three to five years.

C. Discoms impose procedural hurdles

Generators and consumers often cite procedural delays as the critical hurdle to scaling up open access. Regulators reject applications based on technical constraints, like inadequate transmission or the wheeling capacity of the grid. States like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Rajasthan have shown resistance in approving applications for open access.

Recommendation: States have shown reluctance to promote open access due to their inability to protect revenues and reduce losses. Therefore,we recommend planning a phase-wise rollout of reforms starting with progressive states. This will help incorporate learnings before implementing reforms at the national scale.

D. Intermittency in renewable energy injection makes open access more challenging

Intermittency in renewable energy generation does not match the open-access consumer demand, resulting in a mismatch of demand and supply. Under the banking mechanism, regulations allows the facility of notionally parking unused power generated with the discom and using it at a later time.. With an increased share of renewable energy and significant variations, the viability of open access is becoming increasingly difficult for discoms.

Recommendation: Design a new banking framework that standardises banking charges, banking/un-banking duration, and compensation for consumers for excess, balance, or unutilised banked power for renewable energy.

References

- [1] Traditionally, in India, a distribution company (discom) is responsible for sourcing power from various sources—generators or open markets—and supplying it to consumers at regulated tariffs. However, in 2003, under the Electricity Act, the government introduced the concept of open access with the aim of promoting competition and increasing efficiency in the sector.

- [2] As of December 2019, the total installed capacity in the open-access solar market was 3.6 GW, with 1.5 GW projects in the pipeline. (Source: Mercom India)

- [3] Open-access charges include central transmission charges, state transmission charges, wheeling or distribution charges, cross-subsidy surcharge, additional surcharge, SLDC charges, etc.

- [4] Inter-state open access allows a consumer to procure power from a generator within as well as outside of the state of consumption.

- [5] Cross-subsidy surcharge is imposed on open-access consumers primarily as a way to compensate discoms for their loss in revenue.

- [6] An open-access transaction may be of two types, namely captive/group-captive and third-party sale. In a captive/group captive transaction, a consumer sets up a plant within their site or at another’s, and then uses the transmission and distribution network to transport power for their consumption. In a third-party sale, unlike in the captive/group-captive version, the consumer does not own the power plant; the transaction is facilitated through a power purchase or bilateral agreement between the consumer and generator.