Suggested citation: Gupta, Niti, Shanal Pradhan, Abhishek Jain and Nayha Patel. 2021. Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021 – What we know and how to scale up. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

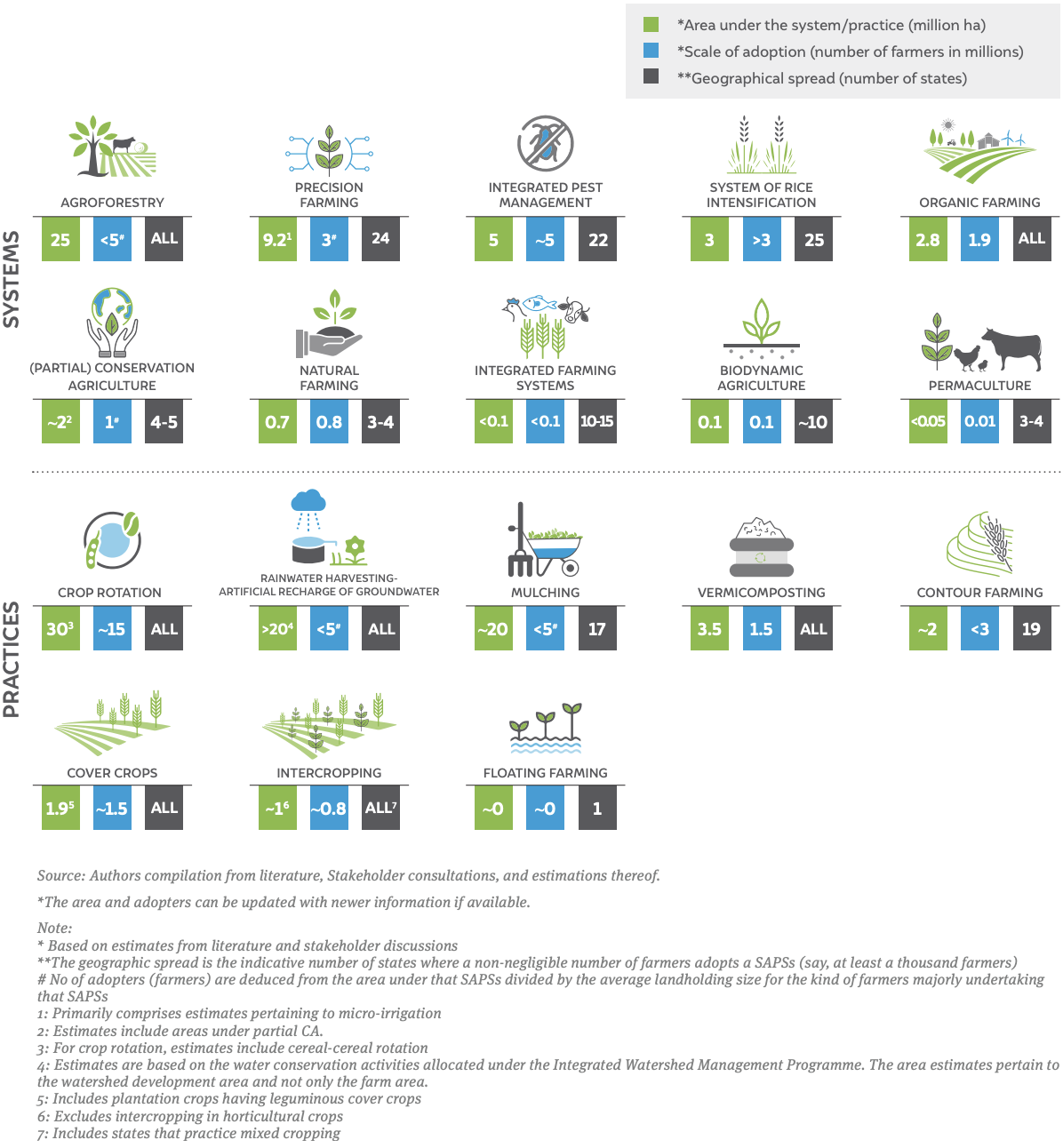

This study, in collaboration with the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), provides an overview of the current state of sustainable agriculture practices and systems (SAPSs) in India. It aims to help policymakers, administrators, philanthropists, and others contribute to an evidence-based scale-up of SAPSs, which represent a vital alternative to conventional, input-intensive agriculture in the context of a climate-constrained future. The study identifies 16 SAPSs – including agroforestry, crop rotation, rainwater harvesting, organic farming and natural farming – using agroecology as an investigative lens. Based on an in-depth review of 16 practices, it concludes that sustainable agriculture is far from mainstream in India. Further, it proposes several measures for promoting SAPSs, including restructured government support and rigorous evidence generation.

Sustainable agriculture practices and systems in India (2021) – key statistics

Key Emerging Themes in India’s Sustainable Agriculture

Click to read more about each practice

Arguably, the Green Revolution remains the most defining phase of Indian agriculture in the last century. An input-intensive and technology-focused approach helped India avert potential famines and meet its food security needs by reducing food imports. While the Green Revolution has ensured India’s self-sufficiency for our cereal needs and has touched most Indian farmers, its long-term impacts are now visibly evident. Be it degrading topsoil, declining groundwater levels, contaminating water bodies, and reducing biodiversity. Crop yields are unable to sustain themselves without increased fertiliser use. Fragmented land holdings and associated low farm incomes are pushing many smallholders towards non-farm economic activities. Maturing climate change science makes it evident that input-intensive agriculture is both a contributor and a victim of climate change.

In the face of increasing extreme climate events—acute and frequent droughts, floods, desert locust attacks—examples of resilience are emerging from the ground, highlighting sustainable agriculture’s potential. For instance, in Andhra Pradesh, during the Pethai and Titli cyclones in 2018, the crops cultivated through natural farming showed greater resilience to heavy winds than conventional crops. While such examples are emerging, the overall understanding of the state of sustainable agriculture at a pan-India level is missing. For example, what sustainable agricultural practices are prevailing across India? Where are they being practised? How many farmers have adopted them? Which organisations are promoting such practices? What impact has such practices had on farm incomes, environment and social outcomes? If impact evidence is not available, then what are the gaps in our current knowledge?

This study attempts to answer such questions to help policymakers, administrators, and philanthropic organisations, among others, to make evidence-backed decisions to scale-up sustainable agriculture practices in India as appropriate.

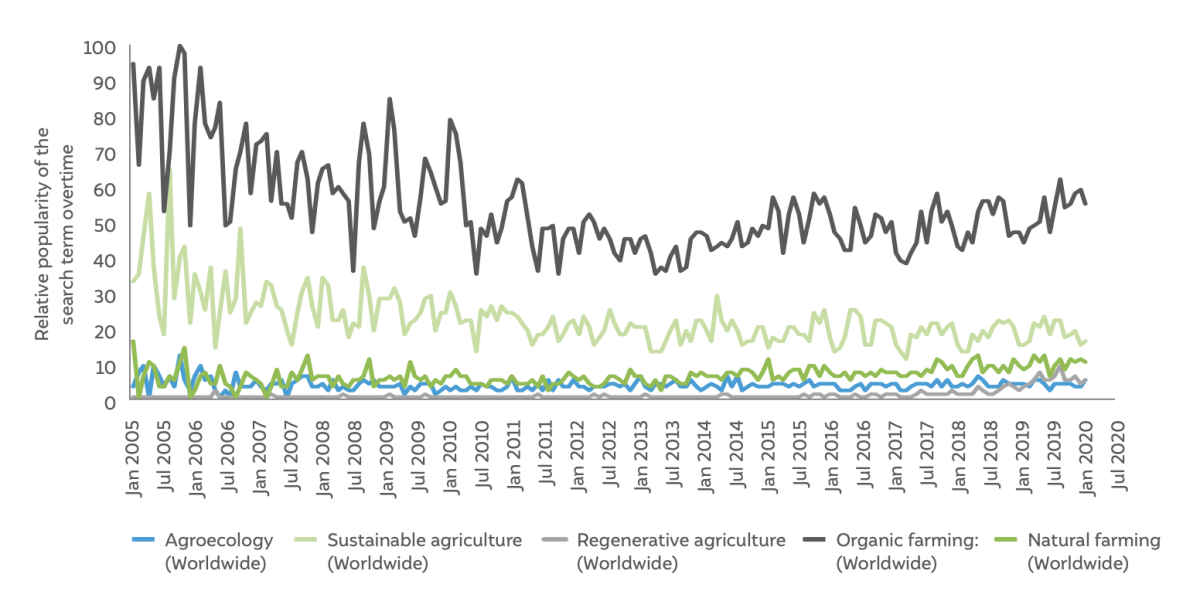

It is important to understand what ‘sustainable agriculture’ is before identifying specific sustainable agricultural practices. As a concept, sustainable agriculture is dynamic with wide variations in its definition and practice. In our efforts to reconcile the concept, we encountered almost 70 definitions of the term. Multiple terms are used to refer to underlying concepts of sustainable agriculture. Let us consider the Google search trends of the last 15 years. Organic farming is the most popular term, followed by sustainable agriculture, agroecology, natural farming, and then regenerative agriculture (Figure ES1).

Figure ES1 Google trends show organic farming as the most popular term worldwide

Source: Authors’ adaption from (Google Trends)

Among various definitions, we selected agroecology as a lens of investigation in our study, as it adequately captures all the three dimensions of sustainability—economic, environmental, and social. Broadly, it refers to less resource-intensive farming solutions, provides more diversity in crops and livestock, and allows farmers to adapt to local circumstances.

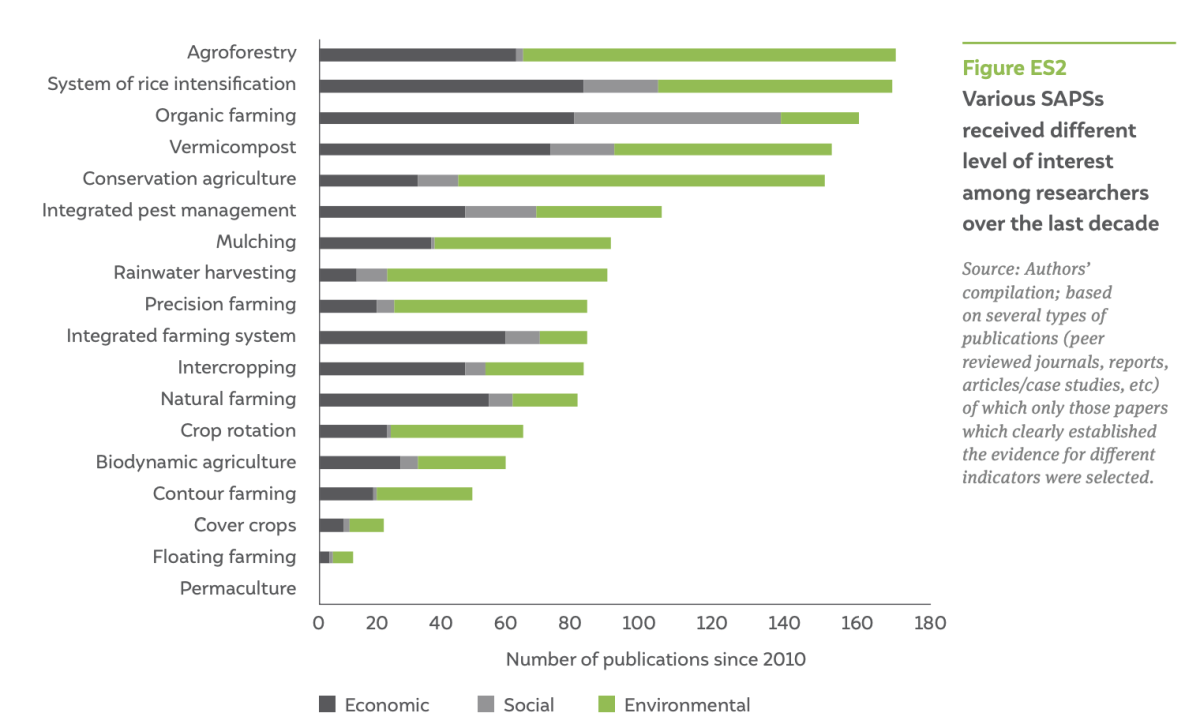

From the systematic review of literature, we find that agroforestry, CA, and SRI are the most popular among researchers assessing the impact of SAPSs on various outcomes (Figure ES2). In contrast, the impact evidence around permaculture and floating farming in the Indian context is almost non-existent. The impact evidence of biodynamic agriculture is also very limited currently. Regarding different areas of outcomes, most of the SAPSs have many publications focusing on environmental indicators followed by economic and social ones. However, organic farming, natural farming, and integrated farming systems have many publications focused on economic outcomes.

While states like Sikkim and Andhra Pradesh are leading the way on sustainable agriculture in India, the adoption remains on the margins at an all-India level. Likewise, the impact evidence about its outcomes on the economic, social and environmental front is limited.

At one end, we must generate more long-term evidence. Alongside, we should leverage existing evidence to scale-up context-specific SAPSs. The scale-up could start with rainfed areas, as they are already practising low-resource agriculture, have low productivities, and primarily stand to gain from the transition. As the positive results at scale would emerge, farmers in irrigated areas will follow suit.

At the budgetary level, significantly increase allocation to sustainable agriculture enabling its evidence-backed scale-up across the country. At the tactical level, focus on region- and practice-wise priorities, which span a wide variety: from technological innovation to help mechanise labour-intensive processes to farmers’ capacity building in knowledge-intensive practices.

Finally, broaden the national policy focus from food security to nutrition security and yield to total farm productivity. It would help recognise the critical role that sustainable agriculture could play to ensure India’s nutrition security in a climate-constrained world.

Policy Study on Re-calibrating Institutions for Climate Action

Millet Mantra - The Culinary Centrepiece of India's G20 Presidency

How to Design Scalable and Sustainable Programmes

Identifying Pathways for Scaling Up Climate-Smart Agriculture